Last week, for my 40th birthday, I visited Elora, the village where I grew up, and which I still think of as “home”. My parents have sold the house, and after they move out it will be much harder for me to visit the village again. So I shot something like ten thousand photos of the house, and of the Elora Gorge. Here are a few of them.

For 31 years, this was my family’s home.

The window in the library – the room in which I decided to be a writer, and wrote my first stuff.

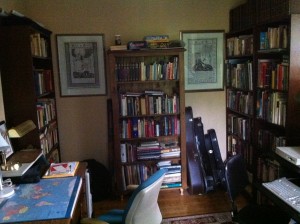

The library. For the computer nerds out there: yes, that is a fully functioning Apple LC-475, on the desk.

A path in “my” forest, the Elora Gorge Conservation Area.

That path leads to this landmark: “Hole in the Rock”. (Such an imaginative name.)

Cedar tree roots growing over a rocky ridge.

The much-photographed merging of the Irvine and Grand rivers, overlooked by Lover’s Leap.

This small plateau is the exact spot where I had a number of “spiritual experiences” (for lack of a better word) for the first time in my life. It is the very place where, at the age of 17, I thought I could hear the voice of Herself, in the trees above and the rapids below. And so I decided to become a philosopher.

I’ll post a few stories of growing up here, over the next few weeks or so, maybe. Meanwhile, here’s my sister Nuala’s very fine story of what our house meant to us. Also, if you will forgive the hucksterism, here is a selection from my 2010 book, Circles of Meaning, in which I described what it means to have a home.

As a child, in my free hours after school, or on weekends when I had no responsibilities, I would ride my bicycle all over every street in my village. Perhaps this is because I had many brothers and sisters, and therefore could not find true privacy in the house. But it’s also true that I wanted to explore the village everywhere, and claim it as my own. My family moved to the village a week before my ninth birthday. By the time I was ten, I knew the streets by the shape of the cracks and potholes. I knew the houses by the friendly and unfriendly dogs that would bark at my passing. I knew the bushes where wild raspberries grew. In the winter I knew the shapes of the snow drifts, and the best toboggan hills, and I knew spring was coming when the cedar trees threw off the snow that covered their boughs. There was a conservation area to the west of the village. It started at the place where the Grand River cut a deep gorge through the limestone, eighty feet deep, and it went on forever. I knew this terrain as intimately as I knew the streets and tracks and parks of the village itself. I knew the sinkholes and shallow caves where I could hide, together with a stash of pebbles to throw at passing tourists. I knew how to race through the trees at top speed without crashing into the crags and steppes. I knew the overlooks and plateaus where I could watch the beaten paths, unseen. I invented names for those places, and stories of battles and romances and escapes from danger that happened there. And I had a regular route that took me to each one, in its sequence, like a sentry on guard. These were my sacred places, and this was my land.

The Elora Gorge Conservation Area is where I made the first intellectual and emotional discoveries which deserve to be called ‘spiritual’. What made the landscape spiritual was not something supernatural: I was not seeing visions or experiencing trance states. Nor was there something new every time I explored it. Moreover, the forest was not untouched by civilization. Paved roads, water wells, stone walls, campsites with electric hook-ups, and other signs of human management could be found everywhere. Some of the landmarks of my route included a ruined stone factory, a ruined mill race, and a hand-pumped water well. (That well, by the way, has been filled in, and an unspiritual pressurized tap in a concrete base was installed nearby to replace it. I’m annoyed.)

Yet I think that I knew, somewhere in my childhood mind, that when I raced through the trees on the riverside at full speed, or when I scaled the cliffs of the gorge without any safety harnesses, or did any number of reckless and dangerous things with no thought of injury or death — on those days I knew that I was strong. What is more — when I set out and ran my regular path from one secret place to the next, and saw that all was in order, I was most truly myself.

One Response to The Town I Loved So Well