Recently, I spent $100 advertising my novels on Facebook for two weeks. Here’s the results so far:

- 13,600 impressions.

- 151 clicks.

- 18 sales of the Kindle editions.

- 3 sales of the paperback editions.

- 0 sales of the Kobo editions.

- More than 200 new “likes” on my Author “fan” page.

- And a handful of extra “likes” on recent entries on my blog.

A few months ago I spent $100 on Google AdWords. The result was broadly similar: around 50,000 impressions; around 250 clicks; but only 27 sales.

Facebook also generated a lot more “buzz” than Google Adwords. More people were talking about the books with me and with each other. I even found a few long-time Facebook contacts who had no idea I was writing fiction, even though I’ve been trying to promote my fiction for several years. So this is good.

But “likes” do not generate revenue. Moreover, after some quick math in my head, I discovered that spending more money on Facebook campaigns might not be helpful. For the campaign to be cost-effective, everyone who clicks on my ad would have to buy at least four of my books.

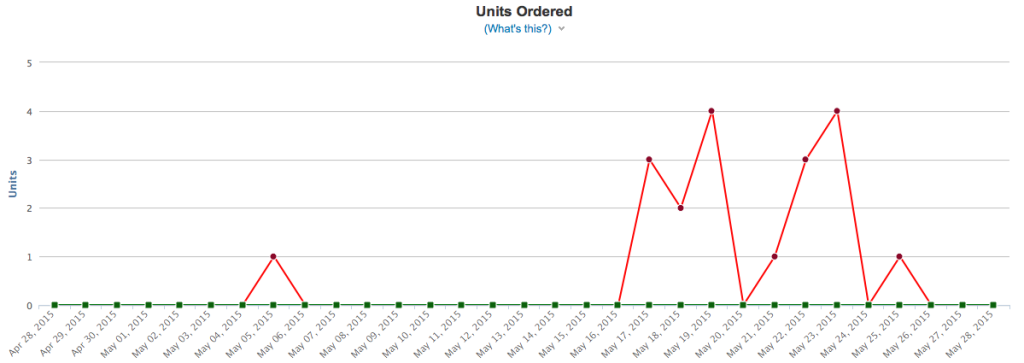

As you can see here…

…that isn’t happening.

I think it’s safe to conclude that automated marketing systems are not cost-effective for independent writers.

There you have it, indie and small-press writers: I spent my money on this experiment so you don’t have to.

Now, I don’t mind spending that much money for such a small result. I have an excellent day job which allows me enough time to write a book and pays me enough money that I can safely lose almost four thousand dollars in the process of publishing and marketing it. (As long as that $4k is spread out over a long time, and not spent all at once. I’m not rich. I’m barely in the middle class.) What I do mind, if anything, is the emotional effect this publicity work is having on me. I’m beginning to resent the way the publishing industry is forcing me to think and talk like a businessman. I resent that my sense of worth as a writer ends up tied to whether I made a sale on a given day. I grow increasingly annoyed at websites and publicity consultants who offer nothing but cheerleading, coupled with dire warnings about financial failure for not going along with the cheerleading. I get angry when publicity consultants tell me I’m bound to get rich as a writer, or when the claim involves weasel-words to the effect that I “might” some day be as big as J.K. Rowling, or that it “could happen” that my books will be made into movies.

I can already hear some of the readers of this blog, some of them writers and artists themselves, clicking the “Comment” button to tell me that if I don’t think like a businessman then my books won’t be read. I’m seeing more and more indie writers treating self-publishing as a path to glory and financial success. Indeed I’m seeing creative writing programs at good colleges and universities releasing graduates who think and talk like competitors in a market, instead of like artists. This is the machine-mind, invading the world of art. The machine-mind is a structure of value priorities which imagines that the production of art could be industrialized, and that the quality of the resultant art could be measured by market forces. I don’t like it.

Some people might be about to tell me that by complaining like this, I’m putting ‘negative energy’ into the universe, or ‘attracting failure’ to myself. No, I tell you, I’m not– and I know this because there is no such thing as negative energy or the ‘law of attraction’. No, really, there’s not.

Finally, I can hear some of my musician, painter, designer, and artist friends prepare to tell me that they should not expect to work for free. You’re right. You should demand that your clients pay you what your work is worth. You’re right to be angry when concert venue managers or literary magazines offer to pay you with “exposure” instead of with real money. I’m not trying to tell you to work for free. I’m attempting to describe a pitfall that the machine-mind takeover of art tried to push me into, so that hopefully the next indie artist won’t get pushed into it after me. The pitfall of irrational expectations. The pitfall of following bad advice. The pitfall of producing bad art.

The first goal of a writer should be to write something interesting, because it is socially or politically important, or thought provoking, or beautiful– or all of those things together. These goals should overlap with the goals of attracting new readers, and creating interesting conversations about the books. But the goal of selling books should actually come second.

Without meaning to sound too self-aggrandizing: I’ve found that the best way to attract attention to a book is to publish the very best work that you can. I learned that lesson by releasing three novels without editing them. They’re edited now: that’s what my third Kickstarter campaign ensured. I also follow a few guidelines for writing better fiction, as detailed in another blog post.**

Only after you’ve written a really good book should you think about promoting it. In case you’re curious, I’ve had the best results promoting my books by doing the following: asking for help from friends and associates; building a mailing list (and here’s where you can join it); and asking for help from people with bigger mailing lists than mine. But I think the most decisive thing an indie writer should do is accept that you’ll never be rich and famous as a writer, then continue writing and promoting your work anyway.

Still, every author writes in the hope, perhaps the faint hope, of being read. I’m not afraid of spending money to promote myself — that was the whole point of buying ads on Facebook and Google, after all — but I want the business end of things to serve the art. It’s the art, not the money, which should be the end in itself.

**

As an aside: I also think it’s important to write in multiple styles and purposes. When I think of musicians I admire, for instance, I think of musicians who have changed up their styles and re-invented themselves several times over long careers. The Beatles, Jethro Tull, David Bowie, Mike Scott and the Waterboys, for instance. There are writers who are similarly varied in the nature and range of their work. Margaret Atwood has written drama, and science fiction, and nonfiction. Neil Gaiman has written graphic novels, fantasy novels, children’s lit, and journalism. Umberto Eco has written historical fiction, and philosophy. I look at these writers and I think, that’s what I want to do, too. Hence why I’ve written fantasy fiction, and poetry, and nonfiction works about religion, human rights, the history of ideas, game theory, climate change, and logic. Fifteen books published so far– the sixteenth will come out this summer. But I digress. So. Carry on as you were.

—

Follow-up, 4th June 2015.

Here’s a video in which renowned fantasy author Ursula LeGuin, making a broadly similar point about the difference between producing a commodity and practicing an art.

And here’s a video in which my favourite musician Mike Scott also makes a similar point about musicians who think and talk like businessmen.

3 Responses to My marketing experiments: and what I think the first job of a writer should be.