Dandelion Wine by Ray Bradbury is a world. It’s the author’s fictitious Green Town Illinois, but it’s also a fairyland where boys are young forever. It’s a town where a new pair of tennis shoes can make boys run and leap like gazelles. Where a mechanical witch in an amusement park was once a real woman, imprisoned in wax for telling true fortunes. Where a boy could be cured of a summer flu with bottled spring air given him by a junkman. Where an old man is a human time machine, and who makes random phone calls to faraway foreign cities so to listen to the traffic and remind himself those places are still real.

But it’s also where death, the Lonely One, hovers over everything. He appears in old age and in murder victims, in machines that fall apart, trolleys that set out for their last run before they are replaced by unromantic buses, and the inevitable return of autumn, and most of all in the darkness of a Ravine that splits the town in two.

What better world can there could be, in which young boys can come of age?

But this blog entry is not just about how wonderful Dandelion Wine is, and why you should go read it. It’s also about why it is a product of its time, for better or worse. As our values change, so do our evaluations of the art of the past, including the recent past. A book or a song or a movie that might have been regarded as beautiful when it was new, might today be regarded as problematic. Here are two ways in which Bradbury’s work is a case study for the point.

First, his style is a richness of imagery. Yet today’s writers are often encouraged to be terse and minimalist: to pack the maximum information in the fewest and simplest words. Stephen King told us never to use adverbs, ever; Dandelion Wine veritably and wonderfully overflows with them.

What would Bradbury himself have to say about the contemporary demands for terseness and minimalism? He would have called it “Tosh!” In a coda published in the 1979 edition of Farenheight 451, he said:

In my story, I had described a lighthouse as having, late at night, an illumination coming from it that was a “God light.” Looking up at it from the viewpoint of any sea-creature one would have felt that one was in “the Presence.”

The editors had deleted “God-Light” and “in the Presence.”

Some five years back, the editors of yet another anthology for school readers put together a volume with some 400 (count ’em) short stories in it. How do you cram 400 short stories by Twain, Irving, Poe, Maupassant and Bierce into one book?

Simplicity itself. Skin, debone, demarrow, scarify, melt, render down and destroy. Every adjective that counted, every verb that moved, every metaphor that weighed more than a mosquito – out! Every simile that would have made a sub-moron’s mouth twitch – gone! Any aside that explained the two-bit philosophy of a first-rate writer – lost!

Every story, slenderized, starved, bluepenciled, leeched and bled white, resembled every other story. Twain read like Poe read like Shakespeare read like Dostoevsky read like – in the finale – Edgar Guest. Every word of more than three syllables had been razored. Every image that demanded so much as one instant’s attention – shot dead.

Do you begin to get the damned and incredible picture?

In this particular case, I think Bradbury has it right, and contemporary minimalists have it wrong. Editors, and for that matter writers, who assume readers are half-illiterate, really must find another job.

By contrast. Some of today’s writers are encouraged to be the opposite of minimalist: they’re snarky and edgy, like howling Ginsbergs, where long-winded metaphors beat you over your head with their cleverness and make you feel stupid for not having thought of them first. That, too, is not Bradbury’s style. His style is full of metaphor, and often invokes the language of infinity, such that simple events and ordinary places take on world-defining significance. Yet his style is also also somehow matter-of-fact about it. In a passage that stood out to me because it reminded me of my town, his Green Town is styled like a ship at sea, and all the residents cut grass and trim hedges like sailors bailing out the water to keep the ship steady and floating. It’s a magnificent piece of writing. Here’s another, where an elderly woman shows two pre-teen boys photos of herself when she was their age:

“It was the face of spring, it was the face of summer, it was the warmness of clover breath. Pomegranate glowed in her lips, and the noon sky in her eyes. To touch her face was that always new experience of opening your window one December morning, early, and putting out your hand to the first white cool powdering of snow that had come, silently, with no announcement, in the night. And all of this, this breath-warmness and plum-tenderness was held forever in one miracle of photographic is chemistry which no clock winds could blow upon to change one hour or one second; this fine first cool white snow would never melt, but live a thousand summers.”

Go read Dandelion Wine if you want to see what a non-minimalist style looks like when it is done right.

Second: Dandelion Wine also has another marker which signifies it as a product of its time. All its characters are white and middle-class, or they can be assumed so because that’s the way white middle class people wrote books back in 1946. It’s a town where men smoke cigars on their porches after work and women bake pies and cool them on windowsills. Today, readers demand representation and diversity, and strong female and POC protagonists. Dandelion Wine was published more than half a century ago, and therefore has none of those things. Further, some of its metaphors jar the modern reader with their contemporary inappropriateness: an old man describes a herd of buffalo by saying they had “heads like Negro’s fists”. Today an editor would be right to jump on that metaphor and erase it immediately. But in 1946, an editor would only ask if it the reader could see the buffalo that way.

What would Bradbury say to the contemporary critic who felt the work was sullied by such things? Again, the coda from Farenheight 451 provides his reply:

I sent a play, Leviathan 99, off to a university theater a month ago. My play is based on the “Moby Dick” mythology, dedicated to Melville, and concerns a rocket crew and a blind space captain who venture forth to encounter a Great White Comet and destroy the destroyer. My drama premiers as an opera in Paris this autumn. But, for now, the university wrote back that they hardly dared to do my play – it had no women in it! And the ERA ladies on campus would descend with baseball bats if the drama department even tried!

Grinding my bicuspids into powder, I suggested that would mean, from now on, no more productions of Boys in the Band (no women), or The Women (no men), Or, counting heads, make and female, a good lot of Shakespeare that would never be seen again, especially if you count line and find that all the good stuff went to the males!

I wrote back maybe they should do my play one week, and The Women the next. They probably thought I was joking, and I’m not sure that I wasn’t.

For it is a mad world and it will get madder if we allow the minorities, be they dwarf or giant, orangutan or dolphin, nuclear-head or water-conversationalist, pro-computerologist or Neo-Luddite, simpleton or sage, to interfere with aesthetics. The real world is the playing ground for each and every group, to make or unmake laws. But the tip of the nose of my book or stories or poems is where their rights end and my territorial imperatives begin, run and rule. If Mormons do not like my plays, let them write their own.

My point here is not only to show how contemporary values change how we enjoy (or do not enjoy) things. It’s also to show that the contemporary debate about representation in literature is much older than most people realise. In one corner of this debate there’s Bradbury who claims the absolute freedom to write whatever he wants, without interference from anyone, and subject only to the judgment of the work’s aesthetic merits. In the other corner, there’s the readers who notice that their gender, their class, their language, their experience of life, doesn’t appear in the literature of our time. These readers have a serious and important point. All voices deserve a hearing; all faces of all shapes deserve to be seen, and everyone’s story deserves to be told, and to be told with all the beauty and tragedy and love that can be mustered in the telling. So if writers are still only writing about Americana, and let us admit that for all its universality Dandelion Wine is a slice of Americana, then where does that leave all other voices? Is their absence a way of saying that those other voices aren’t important enough to be included in our stories? Is it sufficient to say, as Bradbury says, that if you want representation then you should write it yourself?

My other point is, it’s okay to be critical of the things you love. I will likely continue to read and love Bradbury’s work, and I’ll encourage others to love his work as well. But I will also be conscious of what it is. You can read a book like Dandelion Wine with a question in your mind like this one: is the experience expressed in the book important and beautiful enough that you can suspend your criticism of the parts which contemporary values render problematic? Or, is the book’s experience so deeply embedded in its own time that it can’t leap past its own problems and speak beyond its time?

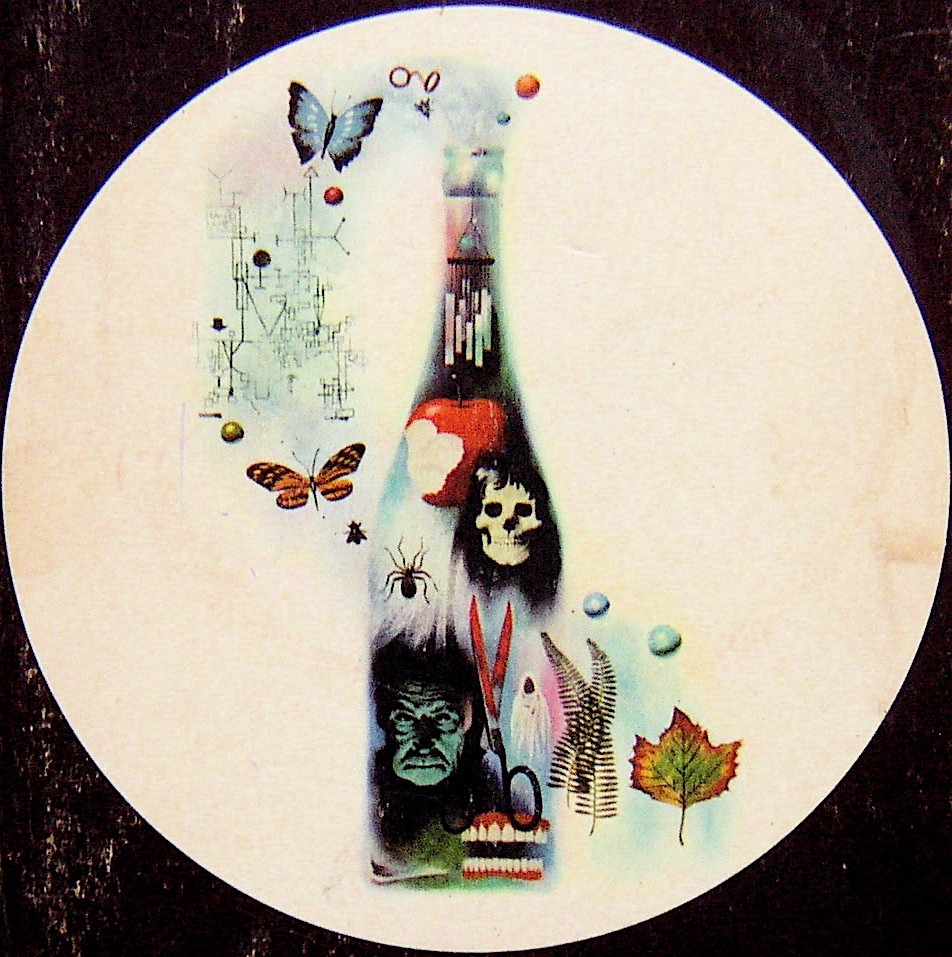

On those last two questions, I think Dandelion Wine is artistically successful, and completely readable today. It is a story where perhaps nothing happens for thirty pages or more, and then everything happens, and it is beautiful and tragic and right, all at once. Death amidst magic; sadness amidst wonder, and yet all of it loving and caring and human. There it is, a whole world in one summer, printed on a page as much as stoppered in a bottle of wine– dandelion wine, no less. It’s a book to read in winter, when you have half-forgotten what summer feels like; or a book to read when you’re old, and want to remember being young again; a book to read when you hear the footsteps of the Lonely One, and it’s time to learn how to welcome him in.