When I was a teenager, my favorite film was Terry Gilliam’s “The Adventures of Baron Munchausen” (1988). It’s about the nature of fantasy, and argues that a life of romanticism and imagination is better than a life of science and reason. It’s titular character makes the argument that:

Science, progress, laws of hydraulics, laws of social dynamics, laws of this that and the other– no place for three-legged cyclops in the south seas, no place for cucumber trees and oceans of wine, and no place for me!”

Later in the film, when one of the villains tells the Baron that he has no grasp of reality, the Baron says “Your reality, sir, is lies and balderdash! And I am delighted to say that I have no grasp of it whatsoever!”

It’s delightful writing. And for a long time, I thought the romantic life endorsed by the film was the sort of life a wise person should want to live.

The defining quality of the romantic is struggle. In the film, the Baron assembles a team of heroes to save a town from a besieging Turkish army. But the Turks are not the enemy, and the film makes it abundantly clear that the Turks live in the same fantasy-imaginal world that the Baron lives in. The enemy is the rational-minded Horatio Jackson, the mayor of the town, who thinks the war can be won through a rationalist world view. At the beginning of the film, he’s failing at it; the war has dragged on for what seems like forever, and some of the townsfolk are confused about why they are fighting or how the war started in the first place. The Baron and his friends save the town in the most absolutely ridiculous way possible, but he dies in the process– and then the film frames the whole thing as the Baron merely telling a story: “And that was one of the many occasions in which I met my death. An experience I do not hesitate strongly to recommend.”

But then the townsfolk open the gates, and find that the Turks have withdrawn, after all. It’s magnificent silliness. I still love it.

But I’m not a teenager anymore. Today I’m a college professor, and the head of my department. I have a PhD, and I’ve written a textbook on logic (and am writing its second edition). I teach and research the history of Western civilization’s art, science, and philosophy. It might look as if I’m on Horatio Jackson’s side now.

The change in my thinking leads me to some interesting questions about things like what a romantic life is really like, whether it’s still possible to live such a life in this day and age, and about the continuity of personal identity over time– the latter question I have known about since my high school days but never fully appreciated until recently.

I have a few answers which I’ll publish some other day. For now I’ll merely observe that I still make time for imagination and wonder, whenever I can: walking in the Gatineau hills here in Quebec or in the hills of Bohemia, Czechia; writing fantasy fiction and science fiction; reading it; learning a new field of knowledge every year. This summer I taught myself the basics of ecology, which I haven’t studied in detail since my grad student days.

I think philosophy and the examined life could be Romantic, in the sense of involving a struggle. Obviously philosophy is about using systematic reason, not fantasy and not mysticism, to reveal the real, the true, the good, and the beautiful. In that sense, I have indeed left the Baron behind. Yet philosophy is also about love, and it’s also about wisdom– such are the roots of the word. And it seems to me it’s not the rational life which is unromantic. It’s the sedentary life, the uncurious life, the life of a passive consumer of other people’s stories (corporate branded, focus-group tested, market-driven), which strikes me as not worth living.

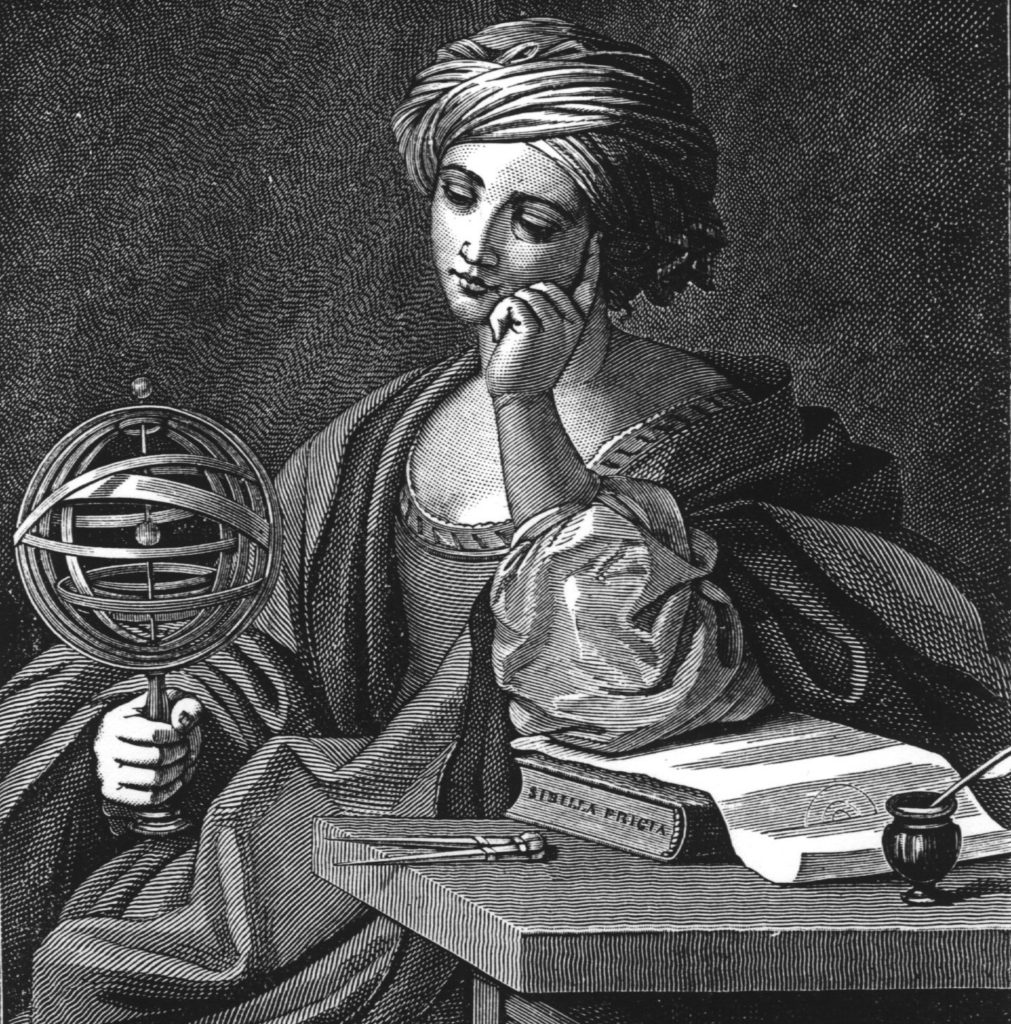

An intellectual, if she’s still curious about things, and still prepared to go wherever her logic takes her, even if it’s to the more frightening and dangerous places, could be every bit as romantic as a fantasy adventurer, or a political rebel.

I’d like to meet more people who think that way.